Despite more cops on the street, New Yorkers in some communities say they don’t feel any safer, and that city investment in housing, education and healthcare would do more to combat crime, according to a new report.

City leaders need to attack the root causes of crime — poverty, inequity and inequality — instead of pouring more money into police and patrol cars, according to residents surveyed in “We Deserve To Be Safe,” a study examining the mood and outlook of people in “overpoliced” neighborhoods.

“The city continues to favor policing as a means to address public safety concerns, despite the community’s demands to end the pervasive, abusive and discriminatory practices within law enforcement agencies,” says the Communities United for Police Reform report compiled by a coalition of social workers, researchers and community leaders.

”It is essential to challenge this flawed perspective to bring about the changes necessary to support all New Yorkers’ welfare and safety.”

The “heavily policed” neighborhoods are in all five boroughs, and include Brownsville, East New York, Stapleton, the South Bronx, the Lower East Side and Jackson Heights.

Many residents of those and other neighborhoods say cops actually contribute to their fear, and point to a long list of innocent or unarmed people killed in clashes with police, including Amadou Diallo in 1999, Sean Bell in 2006, Ramarley Graham, Shantel Davis and Mohamed Bah in 2012, Eric Garner in 2014, Delrawn Small in 2016, and Kawaski Trawick and Allan Feliz in 2019.

“Constant police presence means you live in fear of losing your life to law enforcement 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” said a 54-year-old Black man from Queens, who declined to give his name.

“You are afraid to venture too far from home after sunset. When you hear a siren, you freeze. If you see them following you in a car, you slow down and pray they drive past you.”

His concerns were echoed by a woman who spoke at a town hall event on the subject.

“I’ve gone to the police for help and have instead been ticketed and threatened with arrest,” she said. “’I’ve been robbed and the police have done nothing to help me. My daughter has been robbed and they’ve done nothing to help her. They’ve even refused to help us file a report. Police officers don’t keep me safe. My friends and family keep me safe.”

The debate over police presence even sparked calls in some circles to “defund the police,” a strategy Mayor Adams, a former NYPD captain, has rejected.

“When I go to my communities of color, and I’ve never heard them, never heard them say, ‘Eric, we want less police,’” Adams said shortly after his term began. “My voice cannot supersede the voice of people on the ground.”

But the report’s authors say the boots on the ground approach oversimplifies the strategy of public safety.

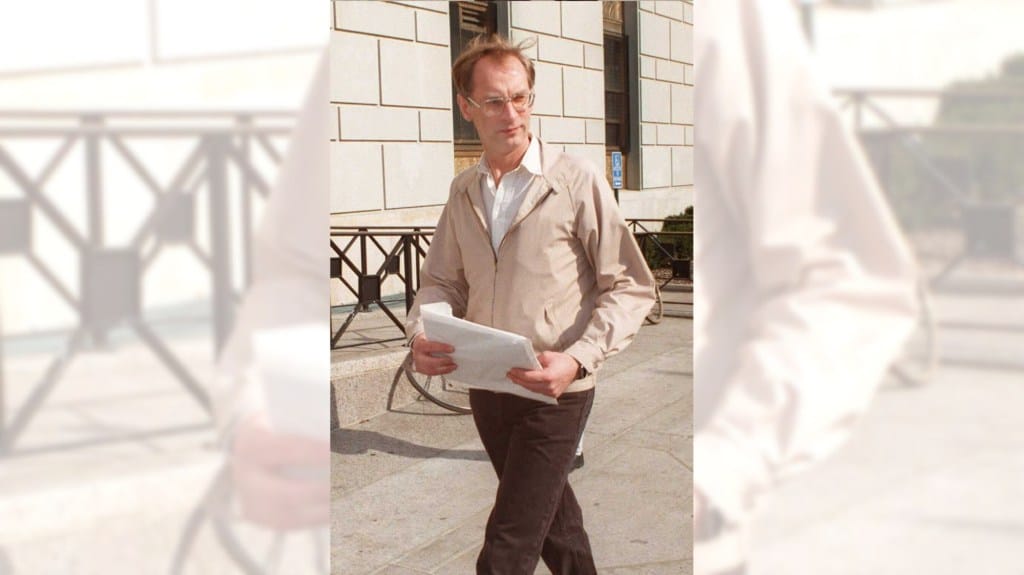

“Participants in the community safety project frequently described a vision of community safety rooted in restoration and investment rather than enforcement and punishment,” said lead author Brett Stoudt, an associate professor in the psychology doctoral program at the CUNY Graduate Center.

The study’s recommendations include addressing systemic social issues, de-escalating conflict, building relationships between the police and communities and investing in crisis intervention programs.

“This city has to get serious about true safety and stop messing around,” said Brooklyn Council member Alexa Avilés, who represents Red Hook and parts of Park Slope and Sunset Park.

“We know true safety is an investment in the things that people need to thrive.”

Originally Published: